FINNS: An Oral History of Finnish-Americans in New Hampshire’s Monadnock Region

Excerpted from FINNS: An Oral History... by Patricia Kangas Ktistes, 1997, all rights reserved.

Chapter 6 - GOLDEN FRIENDS AND DEAREST BROTHERS

Golden friend, and dearest brother,

Brother dear of mine in childhood,

Come and sing with me the stories,

Come and chant with me the legends,

Legends of the times forgotten,

Since we now are here together,

Come together from our roamings.

Seldom do we come for singing,

Seldom to the one the other,

O’er this cold and cruel country,

O’er the poor soil of the Northland.

Let us clasp our hands together

That we thus may best remember.

Join we now in merry singing,

Chant we now the oldest folklore,

That the dear ones all may hear them,

That the well-inclined may hear them,

Of this rising generation.

The Kalevala (1:1-18) translated by John Martin Crawford

Marion (Pakkala) Kangas

Here’s what happened with this society of ours in New Ipswich. The war did more to change our town than anything I can think of. Here we were. We lived in our community, you married the girl next door, and you settled next door, and you had your children and they in turn married the girl next door and settled here and took over Pa’s house or farm or whatever it was. And we didn’t venture far. And here we were, these country people, shipped off to foreign lands. I once thought to get to Fitchburg was a really big adventure. And then to leave home with my little box of clothes. I didn’t have anything. It was really strange. My parents were very Victorian about many things. Many’s the night I cried because I couldn’t stay out with my friends as late as I would have liked to. And yet when it came to that time, I find it very strange that they were willing to let me go. There was no resistance. I think my mother was smarter than she was given credit for. I think she realized there wasn’t much here. What was there for my future? Work in the mill like everybody else.. There were a lot of young people who took the secretarial course and ended out working in the mill because they didn’t want to leave home. But I’m so grateful I had this opportunity. I’m sure if there hadn’t been the war, I wouldn’t have gone. Who knows what my husband would have done for his livelihood? This is where he got his training in the repair of airplanes. During the war with the men gone, the women went and took over the jobs men held. And, of course, industry found this wonderful labor force. They worked hard, they worked diligently, and you didn’t have to pay them much. They did darn good work and they didn’t complain and so this was our step into the new world. I think it’s wonderful that we finally realized that women have a brain and these abilities. Men came home from the service and were anxious to settle down and have a family. But then women were going to school and to college and they weren’t just doing the menial jobs. Just before my future husband, Harvey, went into the service, he always played with the ball team in Fitchburg. And on Sunday morning they would have their basketball games and he would drive me there. After the game we’d go and have our hamburgers and chocolate cream pie: this was a big deal. And we might go to the movies. And on one of these days, December 7, 1941, a newsboy came around while we were having our little lunch and he was talking about Pearl Harbor. And it was a week and a half after that Harvey was in the service—the Army 8th. He was at Chanute and on Long Island. They were learning all about new airplanes. Then he was in England for two years.

I was right out of school when I went to work at Fort Devens. I learned from word-of-mouth that they were giving Civil Service exams and they were looking for typists and bookkeepers and secretaries. Talk about courage: here this little country bumpkin goes around asking for rides from New Ipswich to Fort Devens. I had passed my exam and they promptly hired me. I lived at home for awhile and traveled back and forth with these people who were already commuting. It was necessary thing. All of our young people were already in the service and the government needed people, so they were taking them from the hinterlands.

Then someone told me, “There’s a civilian barracks here for ladies.” Now the civilian barracks were off grounds for the military except if you invited someone into the rec room, but of course, you couldn’ have them in your apartment or bedrooms. I had a roommate from Illinois. Her brother was an officer in the military. We would eat in the main mess hall, half of which was for the enlisted people and the other half for the officers and civilians. It seems to me that later on it started to break down a little bit. The enlisted men had to serve themselves. The officers were waited on and we were waited on. After awhile, it got so we were waiting on ourselves. It seems to me even the officers waited on themselves. I had been going with Harvey for awhile by then. We did correspond. He was in the service for four years. But I was busy having a social life. Even though it was wartime, you’re young, and life goes on. I’m glad that I left home for that while. learned a lot. I probably was one of the few who hadn’t gone on to business school and yet I became head of the correspondence department. I was happy about that. I worked in a hospital and we would have patients coming in, usually by train. They were wounded and they would try to bring them in at night. If people in the community saw how many of their young men were coming home wounded, it would have upset them. So sometimes we worked at night, entering them in, bringing in their records. ‘Course, there were some wounded we never did see. We saw the more ambulatory patients. There would be mental patients. We knew where they went, what section they were in, and we’d always know walking down the corridor: if you saw one of the technicians walking so many steps behind a patient, you knew that patient was Section 8. They had a number of German prisoners of war working there. That was later on. They were working out-of-doors, digging ditches. They were doing some cleaning. They would be working in the kitchen and some of our people weren’t very kind to them. They had husbands and brothers and fathers that were serving and some were lost. But I think the prisoners were very lucky to be in the United States and I understood some of them didn’t go back to Germany. They fled when they got released and stayed here illegally. My parents never had much nut during the Winter War, they sent packages to relatives in Finland. We had to get green coffee beans so it would go across, it took quite some time; they had to roast it there. We sent bicycle tires. I remember saddle shoes were in style and I don’t know who had gotten a pair of saddle shoes here, but they didn’t fit. So people in Finland were happy to take the saddle shoes. We got a letter back: they liked the shoes so much, could we send more? We had to have cardboard boxes to send packages. After everything was packed, we had to wrap them in white sheets, sew the sheets on, and write the address in pen or marker on all sides.

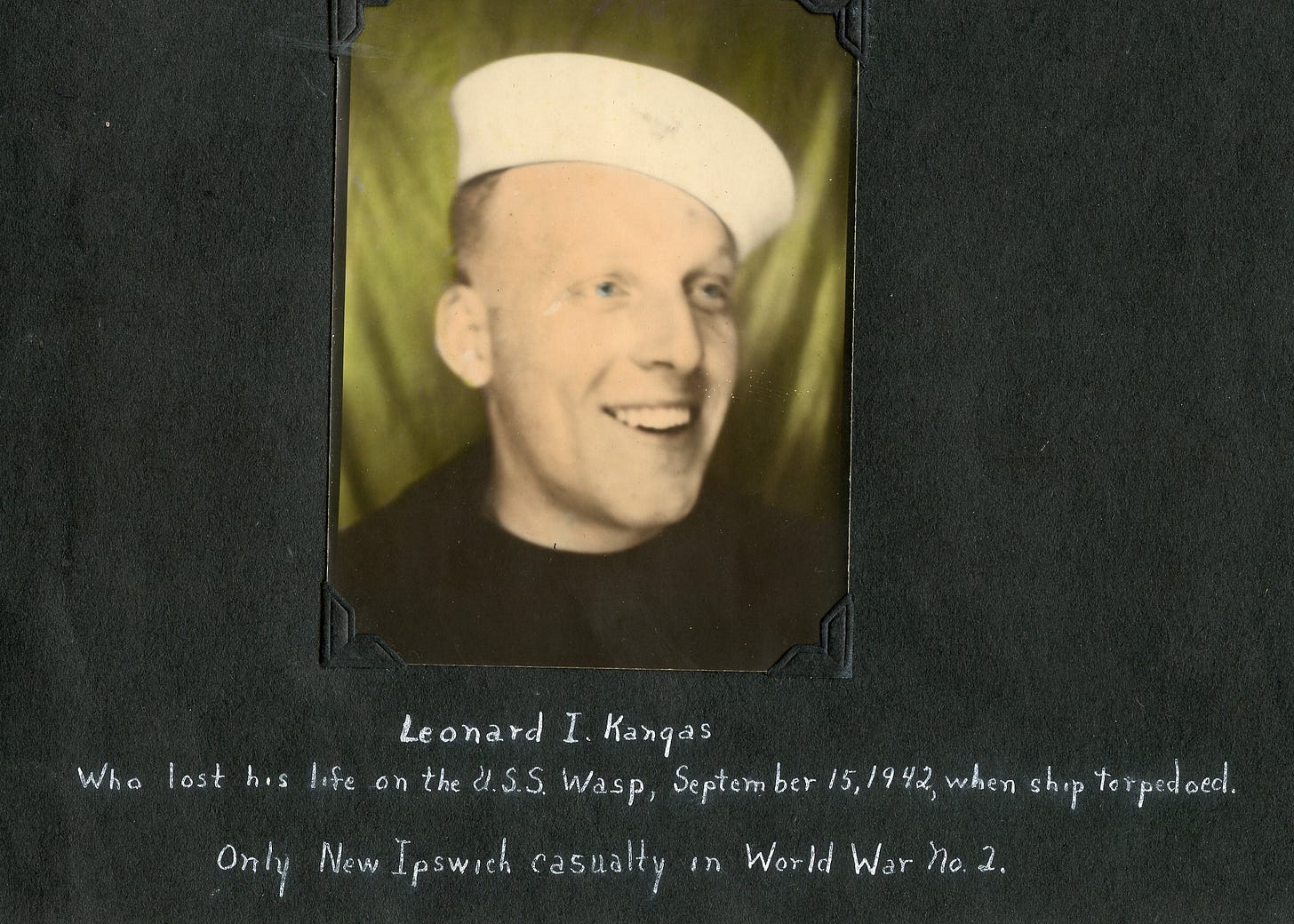

I was still in school when the telegram came about Leonard Kangas missing at Guadalcanal. All the women were a little sweet on him. He had something special, confidence, perhaps because he was a basketball star. And he really was a star: he looked the part. He had that wavy blond hair and such charm.