FINNS: An Oral History of Finnish-Americans in New Hampshire’s Monadnock Region

Excerpted from FINNS: An Oral History... by Patricia Kangas Ktistes, 1997, all rights reserved.

Toivo Kangas

My parents talked about Finland finally being independent. My father’s brother, Uncle Matti, would come over and he and my father would discuss the hopefully better conditions to prevail in the old country for common people. The Finnish government took farms that rich Swedes and Finns owned and gave that land to ordinary Finns so they could start farming because they were losing all their workers just like the rest of Europe. My parents were especially interested in the Finnish war with the Russians. They listened to the news and read reports in Raivajaa but the editors were sort of socialistic. There was one Finn that came to New Ipswich. I don't know if he was just renting for a while. He spoke enough English that he could get by. But as soon as the Russo-Finnish war broke out, he went back to fight the Russians. Russia was a hated guardian angel of the Finns. Many Finns were pro-Roosevelt. We would have been the only democracy left with the Canadians to fight Hitler. We knew already Hitler's motto was ‘Germany today and the world tomorrow.’ These political muckymucks over here preached, “We can’t get into the war, we’ll ruin our democracy.” I thought to myself, “You’re educated but you’re an educated fool.” In the period leading up to the war, the Finns in our area were farming and getting carpenter jobs and picking apples. There were some who had war-related jobs who could get a deferment. I could have made good money in Fitchburg making war materials. Dixie Cup was there and they changed to making war supplies, but I don’t know what they really made. Sugar was rationed, butter was rationed, coffee was rationed, gasoline was rationed. They gave you three gallons a week so you could do necessary things. I used to go to Fitchburg and buy it on the black market. There were two stations that sold gas, all you wanted. Everybody knew that they were selling more than what you were supposed to get. I paid about a buck a gallon—dearly—for it, but I didn’t care. As long as I got my tank full, I was happy even if it cost me three, four, five dollars. It was well worth it.

W E S T E R N U N I O N

BAW21 74 GOVT = WASHINGTON DC OCT 21 1252A

JOHN KANGAS = NEW IPSWICH (HILLSBOROUGH CO) NHAMP =

THE NAVY DEPARTMENT DEEPLY REGRETS TO INFORM YOU THAT YOUR SON LEONARD ISRAEL KANGAS, STOREKEEPER THIRD CLASS US NAVY IS MISSING FOLLOWING ACTION IN THE PERFORMANCE OF HIS DUTY AND IN THE SERVICE OF HIS COUNTRY THE DEPARTMENT APPRECIATES YOUR GREAT ANXIETY BUT DETAILS NOT NOW AVAILABLE AND DELAY IN RECEIPT THEREOF MUST NECESSARILY BE EXPECTED TO PREVENT POSSIBLE AID TO OUR ENEMIES, PLEASE DO NOT DIVULGE THE NAME OF HIS SHIP OR STATION.

REAR ADMIRAL RANDALL JACOBS CHIEF OF NAVAL PERSONNEL

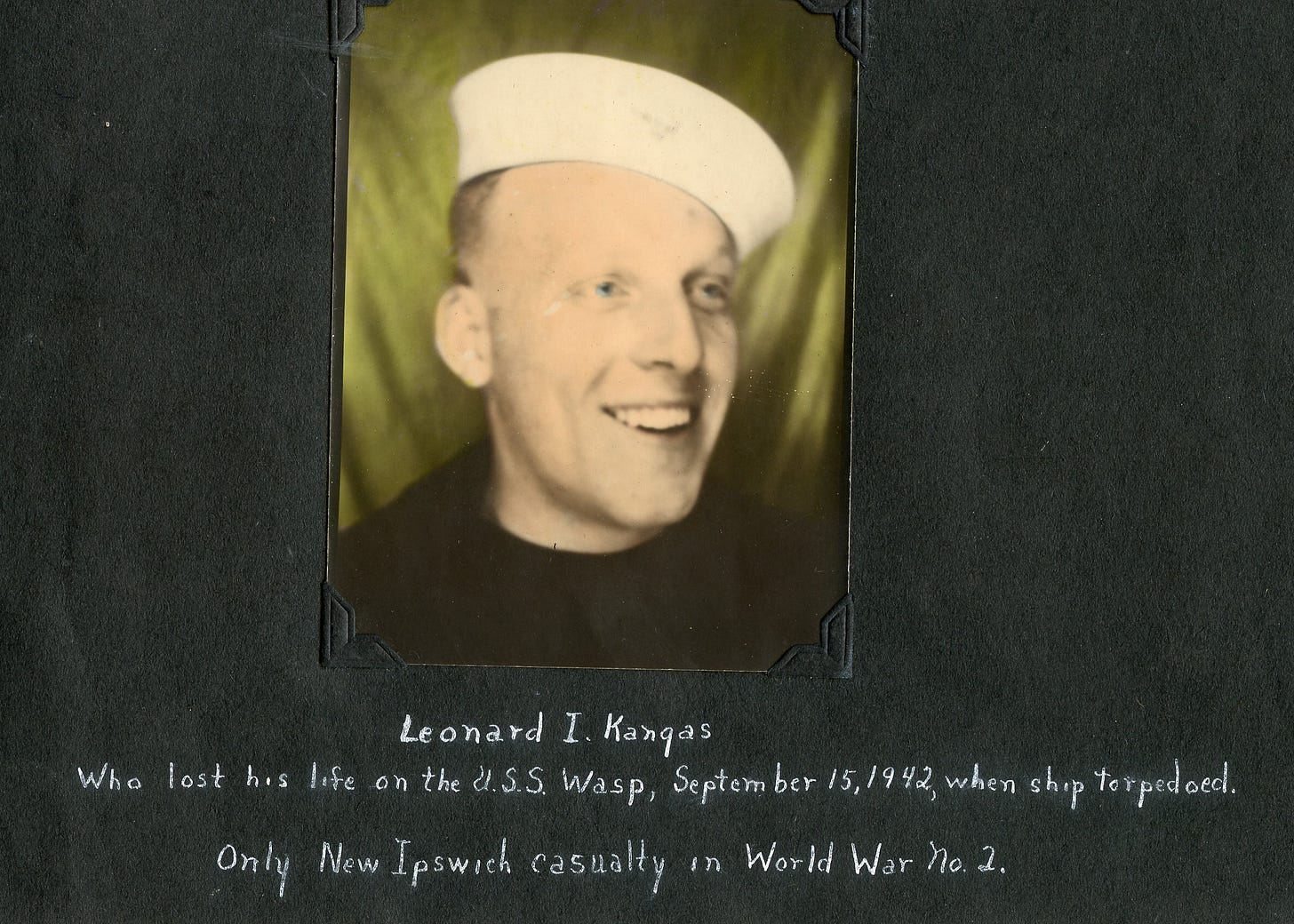

I’ll tell you, when we read that telegram to my mother, it was enough to kill her. It was still peacetime when my brother Leonard enlisted in the Navy, somewhere around ‘38 or ‘39, because there was no future for him in New Ipswich. He and about 200 other boys were killed by a couple of Japanese submarines off the Solomon Islands. So then they sent some legal papers from the Navy Department for me to fill out to collect Leonard’s life insurance. He had a $5,000 insurance policy and I had to take care of that thing and you could hardly find anybody who would help you fill out those types of papers. They were very complicated. I had to go to Boston to get information at the First Naval District office. Then I had to look up where he was born in Worcester. It was John Preston’s father who helped me fill them out. I was sure that Mr. Preston, who was a Harvard graduate, was qualified to do it. He hemmed and he hawed and he said, “Well, I’ll do this for you on one condition: that you get me the information that I want.” I said, “Well, I’m ready to start in right now.” So he told me what to get and it took him about three weeks to fill those forms out. And one time I mistakenly brought him some item that wasn’t really what he wanted and he snapped, “What do you bring that stuff here for? That’s no good for me! Take it back! I don't need that! Get me what I told you to get!” He got a little ugly: one of these old hard-boiled Yankees. Mr. Preston finally completed all the government forms and I gave him a large envelope to send them to the Navy Department in Washington, D.C. In due time, the first insurance checks began to arrive. Everything was filled out right, so I was grateful for his help in getting these papers done correctly. I was grateful for Will Preston being what he was: a very intelligent Yankee gentleman. He told me once, “I’m a widower and I have a cow to take care of and I should have a Finnish wife.” He had seen how these Finnish women worked on farms, just like men, and that’s the kind of ambition he admired.

When I enlisted in the Merchant Marine, I think coming from the Finnish culture kind of held me back because I was afraid to do this and afraid to do that. It sort of had a negative impact. “What am I going to do? Who’s going to support me?” And I got out of that cycle once I went on my own to New York and had to mix in with people and find my own way. New Ipswich was such a closed society, “Don’t do this, don’t go here, this is sinful, don’t go there, be careful.” I just didn’t care to study in school anymore. I wanted to earn some money. I told my mother, “I’m going to get out of this miserable town. When I get up in the morning, there’s no work here to earn money or nothing in this stinking rotten town of New Ipswich.” It was as dead as a doornail. Only farming and work at Walker’s shop making wooden handles. That food on my first ship was so bad. The cook made some hamburg with rice and put a cabbage leaf over that. Generally, that’s good food. But he put some of that same old snake or skunk oil in there. And we opened up the cabbage leaf and smelled it and it was enough to knock you on your rear end. He put it in everything. I don’t know how anyone could eat that. That same day, he had made some tomato stew at noontime and generally any canned tomatoes are good. It would have been a luxury for us to enjoy that, but what a horrible taste! The night we had that cabbage leaf with the rice and hamburg. Most of us threw it through the port hole and gave it up as an offering to King Neptune. Some of the crew were threatening to throw the cook overboard, too, where they thought hebelonged. I was asking this old salt sitting across the table from me, “How in the heck could anyone eat that poison?” And he said, “Well, it wasn’t any worse than that tomato stew when they dropped amiscarriage in it.” So the old salt ate the tomato stew and the rotten hamburg. We found that the foodwas stored right near a supply of creosote. I was four months before I could get leave and get back to New Ipswich and eat my mother’s cooking. Later, we had good food on the Belle of the West. This had a brand-new turbine engine made by General Electric—the noise was just a hum. That was a nice ship: it would steer by itself. You’d set it and pull a lever and it would stay on course. That was high-tech. Before that, ships were fired by oil. But even then, there was smoke with these Liberties. So they’d trap the smoke in compartments right within the ship, in the boiler room. Then at night, they’d open them up and let that junk out so the U-boats wouldn’t see it. When I came back from the Merchant Marine, I went back in the store to work. All the servicemen were expected to get their old jobs back. I got about a dollar an hour but didn’t stay there long. The economy after the war was very good. They started to make automobiles and trucks and cloth and textiles and 1,001 other things to convert to the peacetime economy. There were a lot less Finns farming. A lot had moved to Washington State and Oregon for economic opportunities, cutting lumber and shipbuilding. People also moved to California by the thousands and the Finns were right there with them.

My father Toivo Kangas said the Merchant Marine got little respect although many of them died during the second world war. “They treated us like we were Red Cross girls handing out doughnuts “

Interesting views and opinions of New Ipswich. My father worked at Hedstrom Union in Fitchburg making parts for the P51. I remember the rationing. My father gave rides to others who also worked in Fitchburg.