FINNS: An Oral History of Finnish-Americans in New Hampshire’s Monadnock Region

Excerpted from FINNS: An Oral History... by Patricia Kangas Ktistes, 1997, all rights reserved.

John (Chuck) Kangas

Chuck no longer recalls the day he left Finland for America. His father John was already working and waiting in Worcester for his wife and son. The story goes that Chuck’s grandmother, Serafina (Walberg) Kero, bade her grandson goodbye for the last time: she died in 1919. A friend drove Chuck and his mother, who was leaving the estate on which her family had served as tenant farmers since 1697, to the train station in a horse-drawn wagon.A descendant of this wagon-driver later reported that three-year-old Chuck, beaming, held the horse’s reins as his mother descended the wagon. Mother and son sailed on a Swedish liner, Frederik VIII. Chuck’s father recalled that within three weeks, his son learned to speak English playing in the streets of Worcester.

When my brother Ista (Leonard) enlisted in the Navy, his ship went to England and took on ammunition—guns and all that. Then they went down to the Mediterranean and unloaded. All I know is when he got down to one of those islands in the Mediterranean, it was under British control at the time—they unloaded guns for the British. The Germans were starting to bomb that island. Then his ship came back to the states—to Boston. My wife Ann and I were working in Brookline, Massachusetts, at the time. Ista got liberty and came over to see if he could borrow my car and take it up to New Ipswich. A Pontiac six cylinder—straight six. A good car. Then he left and went to the west coast.

My brother Ralph was also in the Navy. He had kind of a hard time—he was in three invasions. By then I was working down to Norton Abrasives in Worcester—a good place to work, boy. A lot of Finns and Swedes, but if you crossed some of them Swedes, there was trouble. Then my brother Ralph got over here and came up to Worcester and borrowed my car to get up to New Ipswich. Then my brother Harvey went into the Army Eighth. Then he came up to borrow my car to go up to New Ipswich.

Of course they were rationing gas, so I said, “Gee, if you guys can find anybody to get these cash stamps up there, get them because I’m running short.” Of course, down at Norton’s, a lot of guys were getting gas coupons anyway. They drove somewhere or did some kind of a job where they gave you gas coupons. My youngest brother Toivo gave our folks holy hell because they settled in New Ipswich: “Not a thing to do!” He asked them why they couldn’t have settled somewhere like Jaffrey. He was lucky when he went in the Merchant Marine; he went on many ships.

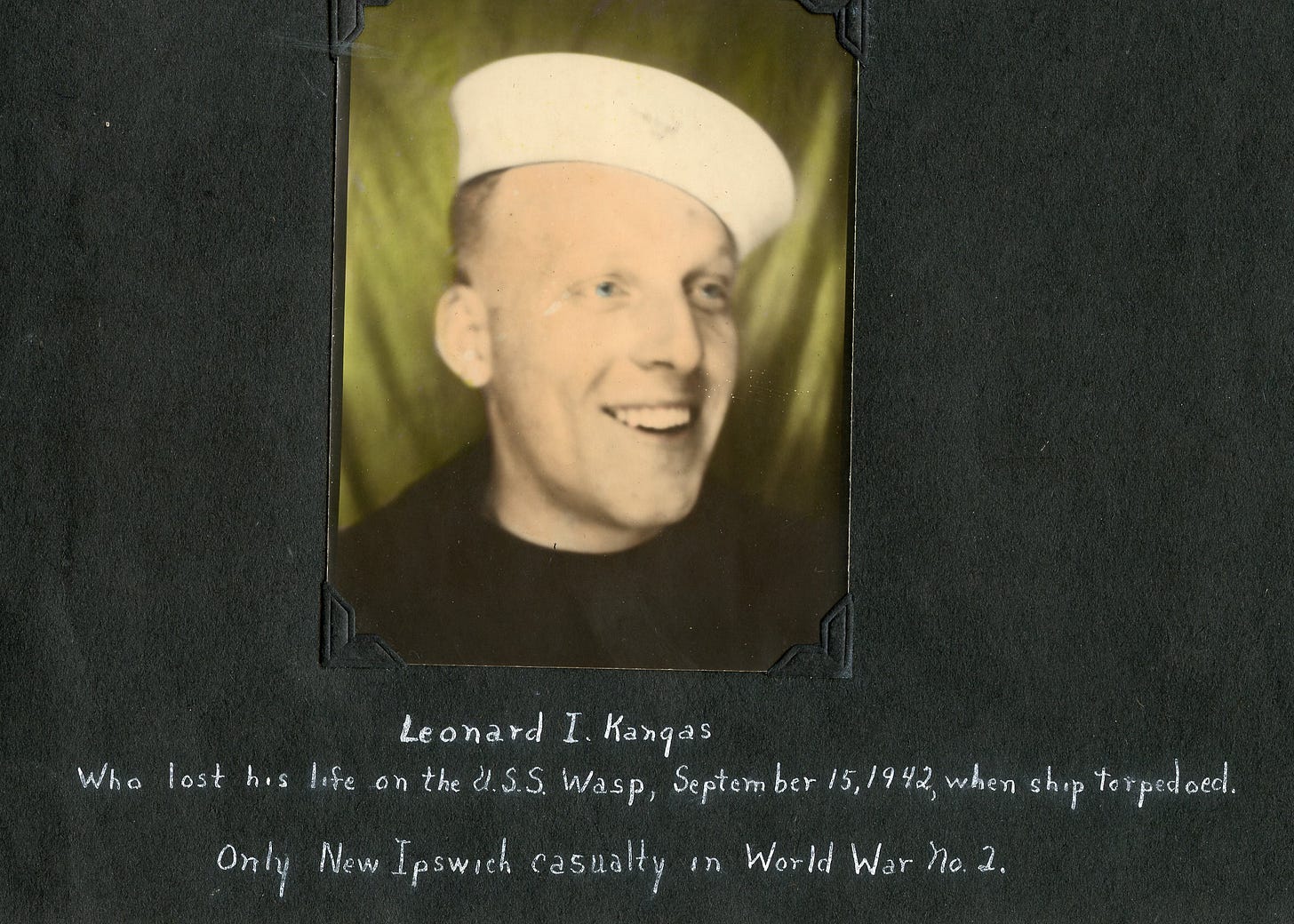

My brother Ista was lost at sea in 1941 on The Wasp. He was a good brother. They were going to Guadalcanal with supplies when their ship was torpedoed. I got a deferment because I was married. But when Ista was killed, I dropped it. My folks hadn’t wanted me to enlist at all. Then when my brother was killed, that made matters worse. A fellow I used to hang around with, Toivo Lahti from Dublin, enlisted in the Seabees [CBs, US Navy Construction Battalion] the same time I did. But I didn’t see him again at all. I told the recruiters I’d like to sign up for the Seabees. There were supposed to be quick advancements. I was about thirty years old and went from fireman first, then second-class machinist. The firemen had a little red stripe on each shoulder. After you got to be a rated man, you got the eagle. Our boot camp was in Williamsburg. I think it lasted eight weeks. They were trying to push as many out as they could. I think I got one weekend off. My wife Ann came down, but we couldn’t go anywhere because I had to get back to camp and she had to get back to Dublin

.The first boat we shipped out on was a one-and-only. An old Norwegian freighter; a rivet job. I think it was over ten days non-stop to reach New Guinea—we went to the southern end and didn’t move. One-hundred-and-fifteen-degree temperatures. We were a supply base for the Navy: Lieutenant Benedict and His 400 Thieves. I had a good wristwatch. I laid it on a bunk and went to take a shower and that wristwatch was gone. Lieutenant Benedict was about as stupid as they come. That’s all he could think of if anyone got into trouble: 10 day, 10 days, and 10 days. In a little brig with a wire fence. They’d throw sailors in for fighting or stealing.

But we had good living. Tents with wooden floors and benches. They had a good chow hall, good cooks. The chief, when any boat came into the harbor, he’d go on board there and take all the food they didn’t want. We were supposed to have one reefer [icebox]. We had four. And they were big ones, too. All full of all kinds of meat and vegetables and everything else. You couldn’t get near the New Guinea natives. They were pretty well guarded. When they went through the camp, they went right through and they didn’t stop for nothing. I don’t know where

our dogs came from, but we had three or four dogs down there. Small ones. I would have like to have taken one home. Smooth-haired fox terriers; they were fed like kings. But the natives were eating dogs and they wanted to swap dogs with us. They had skinny dogs and we had fat, plump dogs with a lot of meat on them. But we wouldn’t swap.

There were some Australians down there. Wonderful people. Boy, if you wanted a beer, they would get it for you. I had a couple of cartons of cigarettes. This Australian came up to me. A beautiful-looking guy. Nice and straight, you know, he was all muscle. “Hey, Mac! You got any Cigarettes?” I said, “Yah. Got any booze?” I gave him two cartons of cigarettes for a quart of booze. No fifths; they had all quarts. But I didn’t care so much for that. They used to give us $3 worth of beer; the alcohol was three-point-two. Down there, I don't know why, but if I drank too much, I used to get a pounding headache out of it. So I quit.

The war was long gone by the time we left New Guinea. One guy was out from New York, “They’ll forget about us guys being in the war.” The war ended in England before it ended over where we were because they were shipping the guys over and they were still fighting up in Okinawa and all over those places. My son Lenny had been born in ‘42. I sent him a sailor suit from California. I bought it, paid for it, gave the address where I wanted it sent. The guy standing next to me said, “You damned fool, what do you want to do that for? He’ll never get it!! My wife Ann got it. I think she sent me a picture.

“Who's that?” Lenny said when I got back home. He was three years old. He wanted no part of me. I’d say he got used to me after probably a couple of weeks. He got around a lot more when I was home. I was driving the car all the time; Ann would only drive it out of necessity. Lenny said we had to get down to Peterborough: a train was coming in. He had to watch the train. After awhile the engineer said, “Why don’t you give me the kid and we’ll drop him off in Jaffrey?” That was a wrong move to make. Then he had to have it all the time. But even that wasn’t good enough; then we had to go to “Swishburg.” A lot more going on; more trains. Ann’s brother Herbie Holmes was living there; he was married to a Fitchburg girl. When I was in the Seabees, Ann got a job. But at first, Lenny was too small. Then she got a part-time job cooking for a family in the summertime. There wouldn’t have been anything to do in Dublin in the wintertime, anyway. She got a job at a big house in Jaffrey Center. When I got back to California, I called her up and told her, “I’m stateside now,” and she quit her job. But the funny part of it was that Lenny had grown up enough so that, like all the rest of the kids, he had to find a puddle of water and he was going to make the most of it. And he got out there and lost his shoes; they looked all over.

They had this Frenchmen: he was on the war board. So Ann went down there to see if she could get another pair of shoes. The Frenchman said, “Shoes? What do you want shoes for? Don’t you realize there's a war on?” The war was over already. The Frenchman didn’t even know that. I don’t know how he didn’t get drafted.

I was fortunate to have talked to a number of survivors of the WASP's sinking and I found out the reason for Leonard Kangas' death. Leonard had been an Appleton Academy and New Hampshire state basketball sensation. On the WASP he was the captain of the WASP's basketbball team and a photo of him playing on the hangar deck is in the official WASP's photos. Leonard and another sailor named Henry Cooper were assigned that day to work in a supply room on the third deck right at the water line. Due to a transcription error when the operational orders were decoded, the WASP's task force had been mistakenly sent right into the location of a Japanese submarine picket line and the Japanese Submarine I-19 fired a spread of 6 torpedoes, 3 of which struck the WASP with the others hitting the destroyer O'Brien and the Battleship North Carolina. The third torpedo struck directly in Leonard's work station. No one came out of that area of the ship alive per first hand testimony. The Japanese submarine commander evaded his own destruction by maneuvering his sub immediately to the aft of the stricken WASP where the sailors were abandoning the ship thus avoiding the US destroyers depth charges. The exact record of these events were kept 'Secret' by the Navy for 30 years after the war ended. Per my father, when George Silver brought the telegram of Leonard's death to the family farm, my grandmother screamed and was inconsolable. She never fully recovered from Leonard's death. Later the government mailed a life insurance policy claim to the family. My grandfather could not figure out all the technical jargon so my father brought the paperwork over to John Preston who was a lawyer and he was able to fill in the application. Leonard's name is on the WW2 memorial on Hampton Beach as well as the Punchbowl Cemetery in Honolulu.