Patricia Kangas Ktistes - Posted on Facebook

Well, dear readers, she's at it once again. Please find below another submission by Linda Dicker Montague:

Thank You for the world so sweet. Thank You for the food we eat.

Thank You for the birds that sing. Thank You, God, for everything.

—A Child’s Mealtime Blessing, recited at Central School

"Do you want to go to school today"?

This question was posed to me in 1957 as a five-year-old. I answered in the affirmative since I was most enthused about getting acquainted with other kids.

Once assigned as a guest to a vacant desk in the first-grade classroom of Miss Persis J. Battis, I was given a phonics book to help me follow the ensuing lesson. Pronouncing verbs, vowels, and other basic components of the English language left me in a state of awe but, heck, here I was with the big kids in first grade.

When let out for recess, I was immediately surrounded by four friendly faces. They belonged to Susan Stacy, Isabel Kangas, Helen Sillanpaa and Walter Flinkstrom, who always liked hanging around with the girls. We played on standard equipment consisting of swings, merry-go-round, and slides. Other kids were playing hopscotch, skipping rope, or rolling marbles on the playground’s asphalt surface.

My Mom, Lily Dicker, had dropped me off that day on her way to do an errand with Mummu, my maternal grandmother, Emma Maki. When Mom returned to collect me, I was asked my opinion of the first-grade experience. Of course, my response was, “I like school.”

The next year, once fully matriculated into the first grade of Mrs. Katherine Shea, the morning began with The Lord’s Prayer and Pledge of Allegiance. We started learning to read on Day One.

Later that fall, as an extracurricular activity, certain of us had to rehearse for the annual Christmas pageant. Some pageant! I was assigned to the triangle-playing section of our juvenile orchestra. Other kids played sleigh bells, tambourines, or—as our non-tonal percussion section—tapped out the beat with sticks whacked against wooden blocks. A couple of teachers stood in the wings, serving as prompters.

Adorned in these theatrical outfits, we sang Christmas carols, tunes about Santa Claus and reindeer, etc. All selections were performed to the piano accompaniment of Music Director Miss Elsie Wheeler.

Do any of you remember the ridiculous red beanies we were required to wear, complete with elastic banding to keep them clamped onto our young heads? And what about the short, one-size-fits-all matching red cotton capes, which probably were lovingly sewn by our mothers?

The entertainment we presented was childish though amazingly our audience was receptive. Had we been attired in green, we could have passed for elves. But the costumes we wore made us look more like Little Red Riding Hood. It was my first stage performance and I’ve been a “show-off" ever since.

As part of a regular school day, hot lunch was served in the cafeteria. A few "cold lunch" tables were tucked into a corner for those who brought lunch boxes, but most kids ate hot lunch.

Before entering the dining room, which assured students of rather basic culinary fare, we each selected a glass bottle of whole milk, enclosed with a cardboard disc. Some kids saved these bottle caps for later use in the playing of tiddlywinks.

Each of the long dining tables had a teacher in command who advised us on table manners and civilized luncheon conversation. After saying grace, we formed an orderly procession to a serving counter, where we were greeted by Mrs. Ellen Somero and Mrs. Marion Davis, our hard-working, cheerful [usually] cooks.

They had to create dishes for approximately 180 days a year with whatever supplies were issued by the authorities. A sample of entrées included chipped beef on mashed potato, Welsh rarebit on Saltine crackers, shepherd's pie, mac-and-cheese, chicken fricassee, American goulash and—on Fridays—fish sticks.

One menu item proved extremely unpopular whenever it appeared: creamed corn. It was soundly rejected by most. We were encouraged to at least try it and managed to, at best, consume one spoonful. We didn’t like the look of the shiny yellow slime, studded with kernels, sliding slow-mo across our plates.

One boy, however, Ernest Goodney, was a creamed-corn enthusiast. When the opportunity arose for seconds, Ernie and a few other brave souls came up to the counter. Mrs. Davis then called out for thirds and finally fourths. Ernie—inspiring for his gastronomic endurance—came running with his clean plate. I don’t know what our cooks did with the leftovers but they should have sent him home with whatever remained in the kettle.

Thank God that every day, two plates stacked with peanut butter-and-jelly sandwiches sat on the hot-lunch tables for those who were hungry, but not for creamed corn. The sandwiches didn’t satisfy as well as hot food, but they were welcome. Keep in mind that for the academic year ending July 1, 1958, the Town Report indicates $3,742.47 was spent on food at Central School.

At recess, the front playground was meant for children in grades one through three. Grades four through six went out the back door to encounter more challenging equipment: tetherball, giant strides, an area for playing games like Red Rover, etc. Adjacent was the athletic field, where we played softball and soccer for outside gym class with Mrs. Lina H. Korpi in charge. Later, M. Lydia Tolman assumed the athletic director position. During foul weather, we had gym in the school basement.

I am grateful to all the teachers and staff, including School Nurse Laila Luhtala, who kept us from such scourges as small pox and polio. My left shoulder vaccination site is still faintly visible after all these years.

I also remember when Mrs. Pearl S. Thompson, our principal, told us we would no longer say The Lord’s Prayer because a Supreme Court ruling had banned its recitation. In 1962, the Court ruled that school-sponsored prayer in public schools violated the establishment clause of the First Amendment.

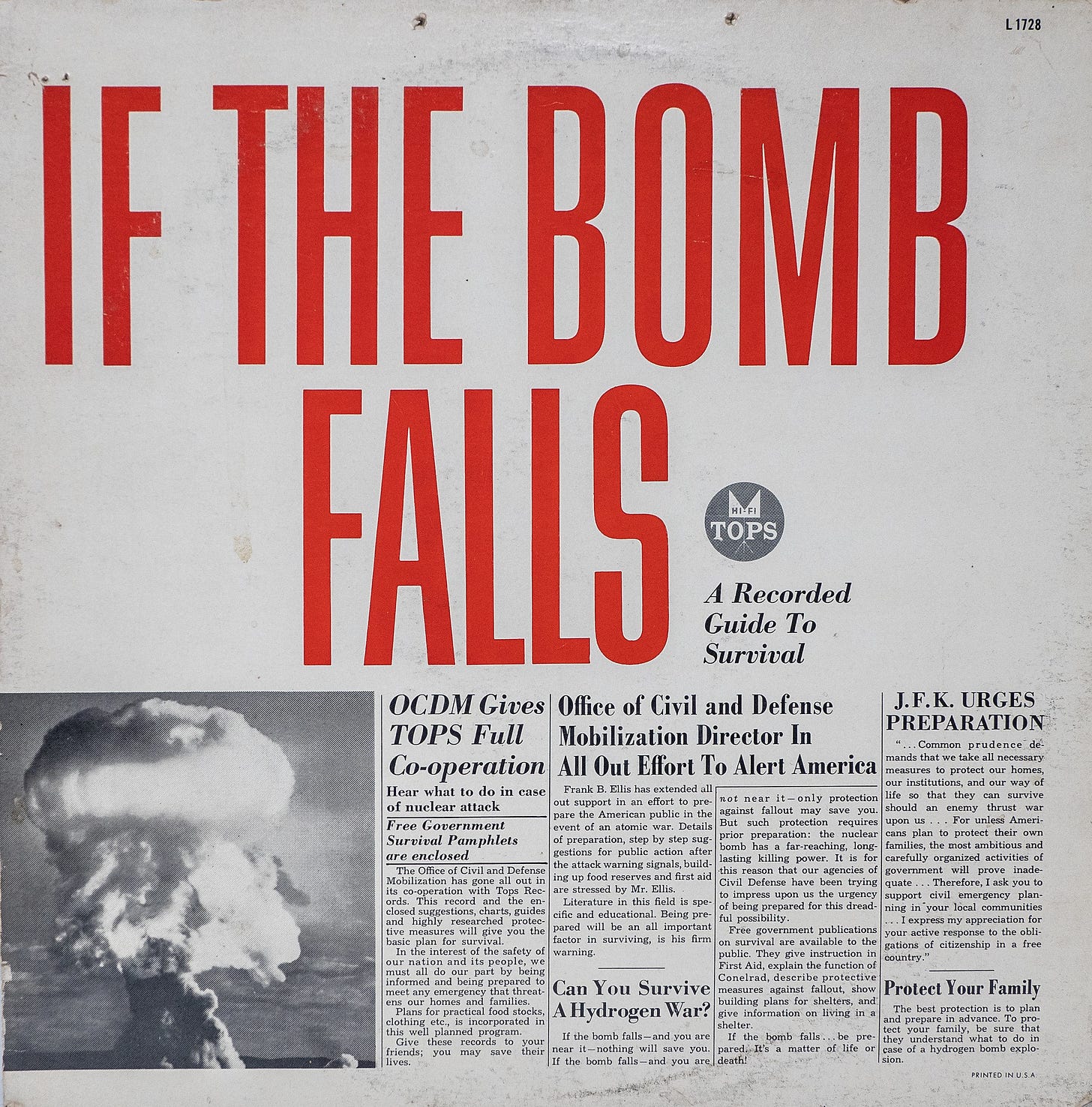

Do any of you recall emergency drills we had to rehearse? We participated in fire drills but also Civil Defense air-raid exercises, especially in times leading up to the Cuban Missile Crisis. Everyone feared nuclear fall-out descending from a Soviet atomic bomb. When a warning sounded, we lined up in the halls to sit cross-legged, facing the wall, heads down, clasping hands behind our necks. This latter move allegedly spared our necks from flying glass. Was such an exercise really going to save us?

As a possible response to the above question, I propose a fictional, dark fantasy about our worst Cold War fears coming true:

THE A-BOMB COMES TO NEW IPSWICH

New Ipswich, New Hampshire, [42.7362° N, 71.8808° W] in 1960 was a peaceful, bucolic Colonial town comprising outlying villages, quaint historic districts, and a good many working dairy and chicken farms. Everyone knew that one could not find a tastier egg than one with a brown shell. This rural community lay at the very heart of New England.

Meanwhile, in Moscow, Russia, USSR, the Supreme Soviet had, in theory, approved testing of a small atomic bomb somewhere in the continental USA. Details were closely held, but Soviet authorities knew such a strike had to be surgical, symbolic, and strategic. Washington, DC; major cities; military sites; and such locations as Area 51 were too obvious as targets. The Americans were half-expecting those places to be attacked and would be quasi-prepared.

After numerous, covert site visits to the USA and subsequent analysis by Soviet agents posing as defectors, the Town of New Ipswich—bastion of smug patriotism—emerged within the collective Communist consciousness as an epicenter of corrupt Western decadence. Geographically, the Town lay proximate to the Northeast Corridor, Canada, and northwest Atlantic.

Culturally, the Town represented all that Moscow despised:

Obsession at the individual level with Capitalist entrepreneurship;

Overt anti-Communism, especially among conservative populations;

Religious fervor—children still prayed before lunch in school;

A bourgeois establishment, business owners descended from mostly Western Europeans, exploiting a proletariat;

Families descended from the British Isles, known for degenerate reverence for royalty over more than a millennium.

First Secretary of The Communist Party Nikita Krushchev believed New Ipswich the ultimate, deserving target for a limited-but-deadly bombing. He slammed his shoe on a Kremlin conference table, screaming that America wasn’t a real nation, but a seething cauldron of mongrel immigrants.

Even Native Americans were suspect as some 17,000 years ago, they’d dissed the area to become Russia by migrating over the Bering Land Bridge to the Americas. Thus, forsaking the Motherland, even prehistorically, proved unforgivable. The more Khrushchev contemplated it, the more his blood pressure rose, causing veins to bulge in his forehead.

New Ipswich—and America—must be punished, especially those pesky, upstart Finns. On Khrushchev’s part, dropping a bomb was a massive gamble, but such a strike might merely result in a proxy war. Khrushchev could ill afford to (again) try to get revenge against Finland, with its history of stubborn resistance and its 800-mile border serving as a buffer against NATO. But the shock and awe of destroying a defiant American Finntown would demonstrate Soviet cunning and daring.

The chosen missile was inscribed on one side with Cyrillic lettering and an identification number. On its other side, in highly polished, mirror-like paint, was an artist's rendition of Krushchev's ugly mug. He looked straight on, displaying his signature smile. The Soviet technicians in charge fondly called the bomb, "Smiling Nikita.”

On the fateful day, shortly after high noon, the roar of approaching aircraft resounded above Hillsborough County. At Central School, an alarm sounded. Students, teachers, and staff ran from the cafeteria to the hallway.

BOOM! went the bomb, on Page Hill Road at the Town Dump. All was consumed in the fiery blast, especially the rats. Gone were the Yankees, Finns, Town Pool, Duke’s Store, saunas, churches, and teenage boys’ souped-up cars, meeting a merciless, catastrophic end. The mushroom cloud could be seen from atop the Empire State Building in New York City.

Back in Moscow, at a celebratory session of the Politburo, Comrade Krushchev was jubilant upon hearing reports of a successful strike. He lowered himself to perform few leg thrusts of the Dance of the Cossacks, nearly splitting the seat of his big-boy pants. To the astonishment of those in attendance, he performed a cartwheel in direction of the door. Finally, waving to and deserting his cronies, he headed for his bomb shelter and kissed his backside goodbye, just in case. He knew that, within minutes America could respond with a bomb but he planned to survive it.

In New Ipswich and environs, all was blighted destruction. However, as the more intrepid media dared approach, a hallowed beacon of hope pierced the gloom. Somehow, miraculously, Central School stood standing and seemed to have escaped relatively untouched. The building’s brick exterior was singed but its occupants appeared safe.

When reporters and TV cameras in hazmat suits entered the elementary school, they found students still in formation, lining the dim halls, hands clasped over necks. The kids appeared unhurt but complained of hunger. One boy, with a very full stomach, lay asleep in a cloakroom.

How had the school possibly been spared? What had deflected all damage from its interior? Could it have been the repellant, reflective properties of creamed corn, served for lunch that day? Who can say?

The moral of this fantasy—now listen to me, boys and girls—is this: ALWAYS OBEY YOUR TEACHERS.

James Roger diary entry

30th November 1912 (Saturday)

Frosty and fair, wind west. David took his guide board and placed in position. Brought grain from Wilbur’s and took manure to Spofford’s and brought sand. I wheeled a cord of wood into church and fixed fires in church and in hall for Finn dance. Got letters from Alice and Hamish, also Mason.

New Ipswich ground zero for the bomb? God forbid. A true observation though that much in New Ipswich represents values that Marxists abhor.

I remember Mrs. Korpi leading us Central School kids in a Christmas Pageant that was held on the stage at Appleton. Dressed up in green tops and red tights on our then skinny little bodies