New Hampshire Times - Feb 6, 1960

The Finnish Community - written by Steve Taylor for the New Hampshire Times

Part 2

One of the earliest acts of the new Finnish immigrants to New Ipswich was to erect a church, hewn log walls on a corner of the Anttila farm. The church was an Apostolic Lutheran Church and served as both a spiritual and a social mainstay of the Finnish community down through the years.

"When you examine the Finnish community in this area you have to be ready to look beyond the stereotypes," says a New Ipswich woman who moved. into the community a dozen years ago and who has watched the town's social and political life closely ever since.

"The first stereotype is that all the Finns here are in the Apostolic Lutheran Church and that they all subscribe to the Biblical literalist theology of that church. There are many Finnish families who don't belong to that church; some belong to other churches in town, and some don't have any church affiliation."

The Apostolic Lutheran Church is a very large church, however, and it has had significant influence within and without the area's Finnish community since its founding.

The American Apostolic Lutheran Church is one of three branches of religious belief spawned by the official Finnish state Lutheran Church and brought to America by immigrants.

Hedbergian Lutherans came to America and eventually affiliated with the Missouri Synod Lutheran Church, which owes its origins to the German Protestant movement and is particularly strong in the Midwest. Hedbergians tended toward a more liberal theological posture..

The second branch is called the Suomi Synod, and is essentially an American extension of the official Finnish state church.

And the third is the Apostolic Lutheran Church, a branch of Finnish Lutheranism that draws extensively on the ideas of Finnish religious philosopher Lars Laestadius as well as Martin Luther, and stands well to the right on the Protestant theological spectrum.

The American Apostolic Lutheran Church is a loose confederation, with local churches having complete autonomy in determining methods of worship and religious practice.

The New Ipswich Apostolic Lutheran Church numbers over 800, making it by far the largest church in the area. It adheres to very conservative interpreta tions of the Bible and the teachings of Christ, and the moral and philosophical principles of the church play a dominant role in shaping the daily life of the membership.

The result is what many outsiders consider to be imposition of extreme puritanical constraints on individual behavior and lifestyles. Birth control and abortion are forbidden, there are no television sets in the homes, women wear no makeup, and socializing with people outside the congregation is frowned upon. New Ipswich's Apostolic Lutherans don't have a paid minister. Rather, worship is led by laymen of the church. Without a paid minister, there is little need for cash so there is no fund raising.

Sunday services normally run two hours, and on communion day will last more than three hours. Other worship activities occur during the week. Hymns, prayers and sermons, some translated from Finnish and others delivered in the mother tongue, are the essential components of worship.

Apostolic Lutherans also include public confession of sin in their worship services. Members may address the congregation and confess sins committed against their brethren or in violation of Christ's teachings. There is also provision for private confession of such sins as adultery.

To the Apostolic Lutheran, membership in the church is not of itself salvation. It is necessary for the individual to awaken to Jesus Christ, to become a "new creature" in a commitment other conservative American Protestants would call "born again."

Social gatherings in the home during the week will often center on sharing readings from the Bible and the writings of Luther and Laestadius, or other church elders. Invitations from other churches to join in ecumenical activities are turned down.

It has been the appearance of clannishness by the Apostolic Lutherans that has created tension in the town in the past.

A particular gripe heard down through the years has been "block voting" by Apostolic Lutheran church members at annual school district meetings. There had long been mutterings about the high birthrate among families who belong to the church and the resultant burden on the local schools.

These have largely disappeared in recent years, most observers say, and tensions have diminished from what they once were.

Attitudes of Finns of the Apostolic Lutheran faith in New Ipswich relative to education seem to be magnifications of those held by Apostolic Lutherans elsewhere in the United States.

"There is the feeling that school is just a necessary evil, and here in New Ipswich there seems to be the least interest in education of any place in the United States," says a prominent church member.

In Finland people worship education, but in America Finns often pull their children out of school as soon as they legally can, he observes.

The Apostolic Lutheran church in New Ipswich has had much ferment in recent years, with various factions vigorously debating each other over the theological direction the church should take.

Some people have left the church and joined another church called the Independent Apostolic Lutheran Church; others have joined mainstream Protestant churches in the area; and still others have become unchurched.

W hen Finland gained independence in 1917. the large scale immigration of Finns to the United States came to a virtual halt, and so too did the movement of native-born Finns into New Ipswich, Rindge and surrounding communities.

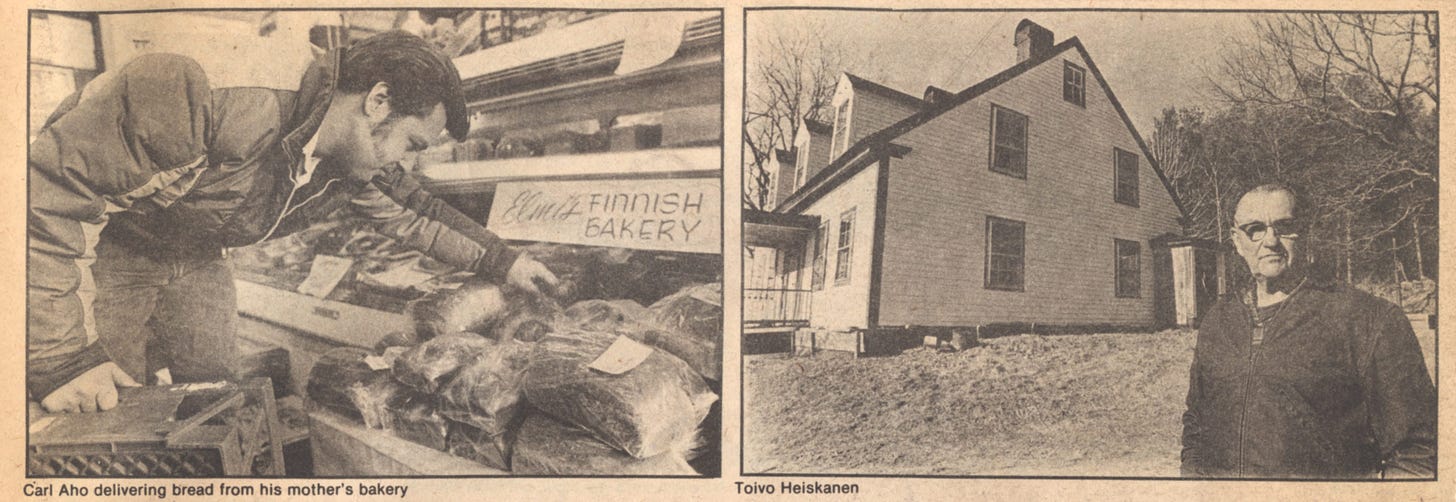

Toivo Heiskanen's parents were typical of the Finnish families who had developed working farms on land that had been given up 25 or 50 years earlier.

"Most of the Finnish people who came here developed dairy, poultry or blueberry farms. Finns don't like to work indoors so farming was a natural way of life for them," he says.

Relations between the Finnish farmers and the Yankees and French Canadians in the area were generally good, Heiskanen recalls.

The Finns had a couple of social clubs that maintained meeting halls in New Ipswich for many years. One of these clubs kept up the Farmers' Hall, a place of meeting for Finnish farmers.

It was here that a group of Finnish farmers got to talking about the low prices they had been receiving for blueberries in the summer of 1926. Dealers had been buying berries from the Finnish farmers for a nickel a basket and then hauling the berries to Boston to be sold for 10 times as much.

[To Be Continued]

James Roger diary entries

22nd September 1912

Fair but cool. Lighted Church fire. Mr. Lord preached from text “Whatsoever a man sows, etc.” S.S. after. 13 Seniors; 1 Junior. Collection: 35 cents. Evening service 7 p.m. Subject: “Pleasures of Sin”; about 20 present. Chas. Wheeler

I think Steve Taylor's article on the Finns in New Ipswich is a good objective analysis and accurate portrayal of life in New Ipswich in 1960, which is actually the year I left New Ipswich. As a student at Northeastern University, I was in the Boston area 12 months of the year because I was a co-op student. Living in Highbridge and visiting my grandparents on Page Hill meant I was straddling 2 communities, the French Canadian one and the Finnish one in the 40s and 50s. Strangely enough I'm more interested in the history of New Ipswich now than I was then. It may be old age and nostalgia.