THE REAL HOUSEWIVES OF NEW IPSWICH

One September evening in 1982, I found myself seated at a table beside a woman of about my age, which was 30. We awaited an orientation for Continuing Education students about to enter Colby-Sawyer College, a liberal arts school in New London, N.H. “Continuing Ed” students were older than those of ordinary college age and brought with them significant responsibilities and life experience.

Colby-Sawyer hadn’t yet gone co-ed, so its mission focused on women. Most incoming students were age 18; in the coming weeks, I’d hear some of them express resentment toward their parents. But I was living the flip side. Prior to leaving home (30-minute commute) for orientation, I’d prepared dinner for my family and ensured our 10-year-old twins did their piano practice and homework.

The woman seated next to me at orientation smiled and introduced herself as a professor. She asked, “So what brings you here? What have you done till now?”

I started to explain I’d been married at 17; became a mother at 20; and was a homemaker and school volunteer. What I’d “done till now” was raise two daughters, grow/preserve food; cook/bake everything from scratch; design clothes/costumes; do yard work and housework; refinish a kitchen floor and tape up drywall; camp with Girl Scouts in the White Mountains; volunteer as a school accompanist; teach a few piano lessons, etc. Recently, I’d devoured the first college textbook I’d ever laid hands on: a borrowed copy of Introduction to Psychology. It exploded my mind.

But on hearing the word “homemaker,” the professor’s smile melted down into a frown. Without waiting for me to finish the sentence, she half-rose in her seat, turned her back to face the opposite direction, and introduced herself to someone else. I sat there, stunned. So even here, admitting you were a homemaker transformed you from a Somebody into a Nobody.

Because I arranged my studies around our family schedule, the choice of majors was limited. Management classes ran 8 to 4, so I chose Business Administration, which also required English courses. Unlike the professor at orientation, faculty in other disciplines didn't care if you had a household to run. If you applied yourself, you were good.

My English composition professors (both men) relished reading essays and stories about working-class lives and Finnish-Americans. But my adolescent classmates—most from privileged backgrounds—didn’t believe the stories. “You don’t really know people like the characters you write about, do you? These immigrants and factory hands and housewives. Right?”

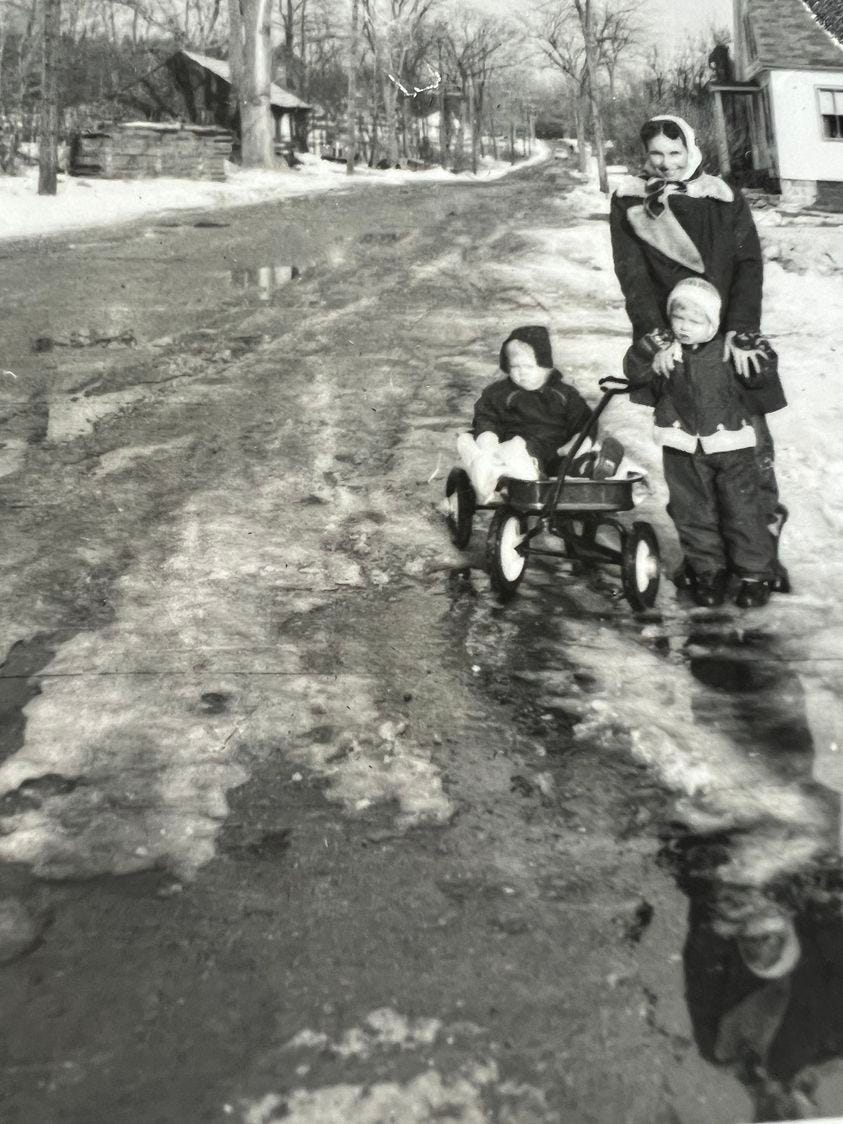

New Ipswich, N.H., where I grew up during the ‘50s and ‘60s, was a motherlode of inspiration. Housewives there weren’t “as seen on TV” in today's so-called Real Housewives reality series. They hadn’t the self-absorbed, exhibitionistic, uber-competitive instincts required for contemporary TV audiences. The Real Housewives of New Ipswich weren’t into vulgarity, one-upping each other, or airing dirty laundry. They were busy upholding civilization.

Prejudice in that era by varying degrees lodged itself in the minds of many males and females regarding women, their perceived limitations, and their “place.” This could be found everywhere, pervading mass media, the workplace, church, in certain aspects of education, even the doctor’s office.

One housewife we knew suffered from a chronic health condition; in despair she consulted her family doctor, a man. She had three little ones in diapers with constant sleep-deprivation, loads of housework, and tons of laundry. The prospect of bearing more babies without a break worried her. Like many others—including my mother—she had a clothes washer but no clothes dryer, dishwasher, drivers license, etc. Year ‘round, she lugged wet laundry to an outdoor clothesline; in winter her hands were raw.

This woman's husband worked full time, controlled the money, and declared he wasn’t “going to be hen-pecked” by temporarily helping his wife. Or finding help for her. So her doctor prescribed that she buy a cheap set of dishes and smash them all against a wall to relieve tension. It never occurred to him that, to follow his advice, she’d have to:

find money in her tight grocery budget for the dishes;

find a babysitter and a ride to the store to buy the dishes;

hope her babies would simultaneously nap so she could throw the dishes without scaring them;

clean up thousands of dish shards and repair the wall;

explain to an unsympathetic husband why she’d done it in the first place before—exasperated—he hauled the whole mess off to the Town dump.

Because of all of the above, instead of throwing dishes, this woman experienced what was called "a nervous breakdown." And she wasn’t the only one.

Another housewife took a long time to work up courage to find a ride to Peterborough and consult a female physician, who she thought would be more understanding. This woman's chief complaint was her exhausting addiction to house-cleaning, compulsively scrubbing everything. When she described how she controlled her “nervous energy," the physician stopped her and snorted, “Nervous? What’s the matter with you women from New Ipswich, anyway? You’re all nervous!”

But not all The Real Housewives of New Ipswich were overwhelmed by balancing households, marriages, and motherhood with personal or professional enrichment. Yes, in many ways it was a man’s world; but a parallel world, propelled by women, revolved in the same orbit. Without it, our universe would have collapsed. While managing domestic enterprises, women served as administrators, artists, clerical staff, choristers, correspondents, educators, entrepreneurs, farmers, factory workers, musicians, scholars, theatre volunteers, Town officers, etc.

James Roger diary entries

17th October 1912 (Thursday)

Fair and warmer wind southwest. David and Daniel pulling apples etc at Jenny Fox’s place. I lit church fire for sewing circle today. Fertilized four lots: Brooks, Willard, Lowe and Donley. Went to mail, David got letter from Mr. Newcomb. I raked some leaves and put some on brooder house. Got letter from Jessie who is coming with Kenneth tomorrow night.

Friends of the Wapack Annual Meeting and Wapack Trail Centennial Celebration

You are invited! Join us as we gather to celebrate the centennial of the Wapack Trail at the Sharon Meeting House, Route 123, Sharon NH. Join us as we gather for this final event of the Centennial year of the Wapack Trail. Our special guest speaker will be Al Jenks

You must register if you plan to attend.

That's a great essay. Life for women and families is a lot different now, but I can't say it's better. We need a happy medium.

Well said Patricia. You sound like my mother. I guess we were lucky to have had homemakers in our homes.