An Apology

I sometimes make misteaks. I missed an entire section of Patricia’s essay yesterday including the part about the comic strip featuring Carl Toko. This is the complete text which is well worth a second reading.

THE REAL HOUSEWIVES OF NEW IPSWICH

One September evening in 1982, I found myself seated at a table beside a woman of about my age, which was 30. We awaited an orientation for Continuing Education students about to enter Colby-Sawyer College, a liberal arts school in New London, N.H. “Continuing Ed” students were older than those of ordinary college age and brought with them significant responsibilities and life experience.

Colby-Sawyer hadn’t yet gone co-ed, so its mission focused on women. Most incoming students were age 18; in the coming weeks, I’d hear some of them express resentment toward their parents. But I was living the flip side. Prior to leaving home (30-minute commute) for orientation, I’d prepared dinner for my family and ensured our 10-year-old twins did their piano practice and homework.

The woman seated next to me at orientation smiled and introduced herself as a professor. She asked, “So what brings you here? What have you done till now?”

I started to explain I’d been married at 17; became a mother at 20; and was a homemaker and school volunteer. What I’d “done till now” was raise two daughters, grow/preserve food; cook/bake everything from scratch; design clothes/costumes; do yard work and housework; refinish a kitchen floor and tape up drywall; camp with Girl Scouts in the White Mountains; volunteer as a school accompanist; teach a few piano lessons, etc. Recently, I’d devoured the first college textbook I’d ever laid hands on: a borrowed copy of Introduction to Psychology. It exploded my mind.

But on hearing the word “homemaker,” the professor’s smile melted down into a frown. Without waiting for me to finish the sentence, she half-rose in her seat, turned her back to face the opposite direction, and introduced herself to someone else. I sat there, stunned. So even here, admitting you were a homemaker transformed you from a Somebody into a Nobody.

Because I arranged my studies around our family schedule, the choice of majors was limited. Management classes ran 8 to 4, so I chose Business Administration, which also required English courses. Unlike the professor at orientation, faculty in other disciplines didn't care if you had a household to run. If you applied yourself, you were good.

My English composition professors (both men) relished reading essays and stories about working-class lives and Finnish-Americans. But my adolescent classmates—most from privileged backgrounds—didn’t believe the stories. “You don’t really know people like the characters you write about, do you? These immigrants and factory hands and housewives. Right?”

New Ipswich, N.H., where I grew up during the ‘50s and ‘60s, was a motherlode of inspiration. Housewives there weren’t “as seen on TV” in today's so-called Real Housewives reality series. They hadn’t the self-absorbed, exhibitionistic, uber-competitive instincts required for contemporary TV audiences. The Real Housewives of New Ipswich weren’t into vulgarity, one-upping each other, or airing dirty laundry. They were busy upholding civilization.

Prejudice in that era by varying degrees lodged itself in the minds of many males and females regarding women, their perceived limitations, and their “place.” This could be found everywhere, pervading mass media, the workplace, church, in certain aspects of education, even the doctor’s office.

One housewife we knew suffered from a chronic health condition; in despair she consulted her family doctor, a man. She had three little ones in diapers with constant sleep-deprivation, loads of housework, and tons of laundry. The prospect of bearing more babies without a break worried her. Like many others—including my mother—she had a clothes washer but no clothes dryer, dishwasher, drivers license, etc. Year ‘round, she lugged wet laundry to an outdoor clothesline; in winter her hands were raw.

This woman's husband worked full time, controlled the money, and declared he wasn’t “going to be hen-pecked” by temporarily helping his wife. Or finding help for her. So her doctor prescribed that she buy a cheap set of dishes and smash them all against a wall to relieve tension. It never occurred to him that, to follow his advice, she’d have to:

find money in her tight grocery budget for the dishes;

find a babysitter and a ride to the store to buy the dishes;

hope her babies would simultaneously nap so she could throw the dishes without scaring them;

clean up thousands of dish shards and repair the wall;

explain to an unsympathetic husband why she’d done it in the first place before—exasperated—he hauled the whole mess off to the Town dump.

Because of all of the above, instead of throwing dishes, this woman experienced what was called "a nervous breakdown." And she wasn’t the only one.

Another housewife took a long time to work up courage to find a ride to Peterborough and consult a female physician, who she thought would be more understanding. This woman's chief complaint was her exhausting addiction to house-cleaning, compulsively scrubbing everything. When she described how she controlled her “nervous energy," the physician stopped her and snorted, “Nervous? What’s the matter with you women from New Ipswich, anyway? You’re all nervous!”

But not all The Real Housewives of New Ipswich were overwhelmed by balancing households, marriages, and motherhood with personal or professional enrichment. Yes, in many ways it was a man’s world; but a parallel world, propelled by women, revolved in the same orbit. Without it, our universe would have collapsed. While managing domestic enterprises, women served as administrators, artists, clerical staff, choristers, correspondents, educators, entrepreneurs, farmers, factory workers, musicians, scholars, theatre volunteers, Town officers, etc.

For example, my Aunt Dot Somero matriculated at Keene Teachers College [KSU] after high school. She took a break to marry my Uncle Martin E.M. Somero and they made a home on Lower School Street. As a young mother, she learned to drive and returned to college. She had no money for fashionable outfits and wore cotton house-dresses to campus. She still graduated with honors.

Some “stay-at-home” moms weren’t home all that much. Those with cars chauffeured other women and their kids. Housewives ran Halloween parties and church youth groups. They helped coaches with youth sport teams and sliced up fresh oranges for softball players. They co-organized Memorial Day parades and the Children’s Fair and worked the tables in Town Hall. They were den mothers to Cub Scouts and leaders of Girl Scouts, taking us shivering on winter hikes and showing how to build campfires and make Hobo Stew and toast marshmallows.

A shining example of such leadership was Joyce Gillam, who had four kids of her own, a house and small farm to run, and a knack for infusing responsibility in even the most goofy, immature Girl Scouts. Famed for her Never-fail Chocolate Cake, she could stretch a dollar in more ways than any of the strutting, prime-time Real Housewives could imagine. It would have been fun to watch Joyce whip today’s whining, bling-studded “reality” stars into shape.

You could say the corporate vision of The Real Housewives of New Ipswich was a fulfilling life for family and friends. Their mission: building a community to support that vision. Their goals: financial security and raising solid citizens. Their strategy: practicing fiscal responsibility and ensuring kids learned self-discipline and independence. Their tactics: guiding us through setbacks; meting out tough love; and promoting a secure environment in which to grow.

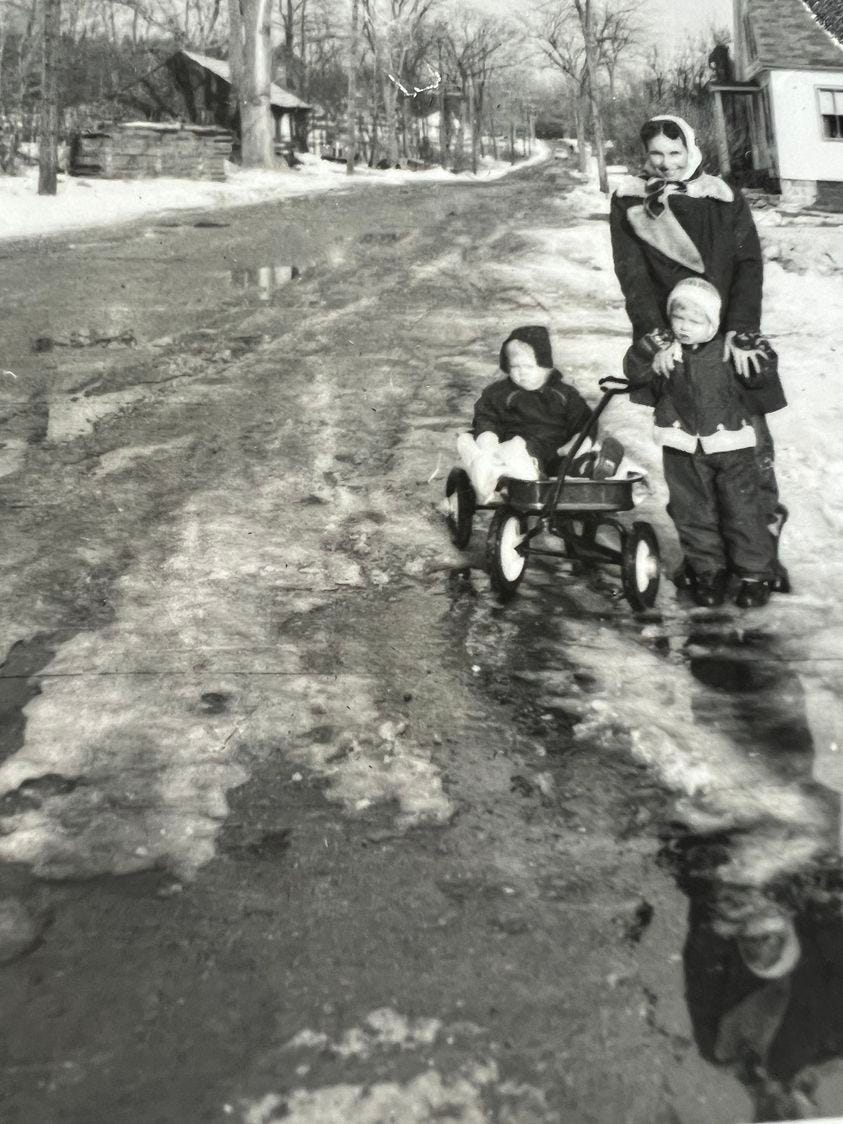

Our family for years lived in the “Flats,” across the road from the Town Pool, tennis court, and ball field. This neighborhood featured modest older homes and mid-century ranches with picture windows: few secrets were kept in that fishbowl. Everybody knew everybody else, including their pets, unto the third or fourth generation. We had real winters, so spring thaw was cause for celebration. Long-suffering fathers could cease putting chains over snow tires. Mothers could pull wagons, loaded with babies, along Temple Road. Kids could roam through barns, cemeteries, woods and over frozen ponds. They’d head home only when the Town clock chimed or their mothers, wearing aprons, stood at the door and called. In the Flats, you could hear a chorus of mothers’ voices echoing across the fields.

One day, as a young child playing in the melting snow, I watched two familiar teenage girls stroll by, dodging puddles, turning to check for traffic. When about even with the entrance to the Town pool—and upon seeing no cars—they whipped open their winter coats, revealing only swimsuits underneath. They turned toward the sun and, for a golden moment, basked bare arms, legs, and necks. Then they clutched their coats shut and doubled over, laughing hysterically.

If someone fell ill, The Real Housewives of New Ipswich circled the wagons. I was about six when my mother, Eleanor Kangas, suffered an early-term miscarriage. My father Toivo worked second shift at Tricnit Hosiery Mill and wouldn’t return till late. Our house suddenly filled with the fragrance of soap and light perfume. Neighbor ladies arrived, bringing food and, tiptoeing in and out of her bedroom, tended to my mother. There was no 911 and no doctor; these women knew what to do. As the eldest child, I thought I could escape it all for awhile by exiting the back door. One alert lady followed and put her arm around me. Losing a baby, she explained, sometimes happens for a reason. Don’t be sad, she said, because your mother will be okay.

But staying home didn’t mean you were isolated because commerce came to you. Toko’s State Line Dairy delivered in the morning. I marveled how someone could have their name, like Leo V. Toko, printed on bottle caps. We kids created a comic strip about Leo’s son Carl, flying through his milk route aboard an airborne toboggan, singing a jingle to the tune of “Goober Peas.” That song had been broadcast over WBZ, pouring forth from the radio atop our refrigerator.

Walter Paajanen appeared in our living room to fix our troublesome TV. He’d unpack a tote full of glass tubes, wire, and tools. As he worked, he offered observations on old-time religion, new scientific advances, and every topic in between. He’d kneel for hours on our braided rug, deciphering technical difficulties. My mother, wringing her hands as the hour grew late, wondered if she should invite him to eat. Finally, his wife Ida would call—sometimes twice—to plead that Walter be sent home. His supper was getting cold.

The Avon lady, Gloria Norton, supplied my mother’s favorite lipstick so she wouldn’t look, in her own words, “like a pale ghost” when she went out. Another convenience was rural mail service. You could put an addressed, unstamped envelope and a dollar bill in your mailbox: the mailman would stamp the envelope for you and leave more stamps and change. Electrolux and Fuller Brush men arrived to demonstrate products. I worried as they scattered dirt on our linoleum floor, over which my mother obsessed. The salesmen showed how their devices made dirt disappear. The United Cooperative bakery truck, wafting an aroma of fresh bread, was driven by Eino Heikkila, another Temple Road resident. My mother welcomed the sight of Eino but not so much that of George R. Standley, whose vehicle, loaded with seafood, was a weird underwater green.

Mr. Standley stopped in the driveway, jumped out of the truck, and, with a clang, hung a battered metal scale out his side door. Some folks recall he perpetually clenched a pipe in his teeth. My mother never mentioned this though she despised smoking. The habit of Old Man Standley’s that really drove her crazy was his propensity to drip fresh fish juice all over her kitchen floor. She finally trained him to bring the haddock, wrapped in paper, only as far as our kitchen steps. Armed with an old towel to catch the drips, she’d meet him there to haul in the day’s catch herself.

My mother’s paranoia over fish drips lay in Obligation. We heard that word a lot in Finnish-American circles. When visitors arrived—even unexpectedly—you were obliged to offer refreshments in a clean home while pretending it was effortless. My mother knocked herself out anticipating guests who would arrive bearing gifts, such as a jar of Avon hand creme. Obligation required you to never arrive empty-handed. This in turn obliged a hostess to serve something nice to eat with coffee, Sanka, or Postum. My mother was indignant when Yankee friends served only crackers and cheese. She served only her best treats even if it meant our family went without. Obligation likely hearkened back to our forebears in Russian-occupied Finland, where people were starving and sacrificial hospitality was a matter of life and death.

Aina Parhiala, who lived atop Town Hill and cultivated gorgeous gardens, was an icon. You could randomly drop in on Aina who, laughing and shrugging off compliments, would produce a spread of homemade delicacies at a round dining-room table with its lace cloth. Nisu [cardamom-flavored sweet bread], blueberry pie, or raspberry coffee cake with berries from her own patch. My mother thought Aina talked too much about produce she grew. After all, Obligation dictated that you spare guests from thinking that hosting them was work, thus making them feel guilty and therefore obligated. But upon seeing Aina’s stocked freezer, I vowed one day I’d grow food and bake stuff from it too.

I was married after my junior year in high school. Two years prior, my parents had moved our family out of state and I grew homesick. I returned to N.H. and after the wedding spent my senior year at Wilton, where my husband and I found an apartment we could afford. In 1970 as I was about to graduate, the Wilton principal asked if I were going on to college. I replied I hadn’t the money. “If you don’t go now,” he warned, glowering, “you’ll never get there.”

Flash forward to 1984, the start of spring semester during my sophomore year at Colby-Sawyer. My parents had driven up for Sunday dinner to find textbooks piled on the kitchen floor. Dinner was ready and the place was clean but disorganized. Obligation had gone out the window. Neither parent had gone to college and they were shocked at how fried I looked. I assured them I’d already survived three semesters and could recuperate over summer since I’d stopped gardening.

Unconvinced, my father—who had hardly ever yelled at me—now shouted, “You’ve got to decide if you’re going to be a college student or a housewife!”

He didn’t understand that—right under his nose—The Real Housewives of New Ipswich had shown how to be both.

James Roger diary entries

18th October 1912 (Friday)

Fine mild day wind west and southwest. David picking apples in orchard in forenoon, and went for grain etc. in afternoon. Got letter from May and Barbara is sick with pneumonia, but doctor is satisfied with condition. Got letter from Hamish. Jessie and Kenneth came by last train. Got PC from May, Barbara going on favorably.

Friends of the Wapack Annual Meeting and Wapack Trail Centennial Celebration

You are invited! Join us as we gather to celebrate the centennial of the Wapack Trail at the Sharon Meeting House, Route 123, Sharon NH. Join us as we gather for this final event of the Centennial year of the Wapack Trail. Our special guest speaker will be Al Jenks

You must register if you plan to attend.

Thank you and all the others too. It just goes to show that children in the community are watching and listening to everything that goes on. They learn what they live. Adults might think they themselves are just doing their jobs as parents and community members but the kids take it all in and form their own conclusions.

Sounds like the New Ipswich I knew in the 40s and 50s. Great story. I knew many of the people that were mentioned. The Paajanens, the Tokos, the Parhilias, George Standley, the Someros, and others. Great memories. My mother married in her junior yr of high school (Appleton) and never finished. She worked for Tricnit at home with a Tricnit installed looping machine, opened up a Luncheonette, later a general store (she was the force behind these ventures, my father helped to make it happen).

On the side she raised 6 children. Yes, New Ipswich had real housewives.